If I must leave

Published:

I didn’t do Maths for my A-levels – all my subjects were in the Humanities. So when I went to UChicago for my undergrad, I fully intended to be a Phil/Econ double major. Sometime during my 2nd year, the Econ major changed to a Math major instead. There were various push and pull reasons about why I chose maths and stubbornly clung onto it for this many years, but one of the main reasons was the people. I realised how much I genuinely liked and enjoyed mathematicians as people. I remember going to my first Beer Skits (invited by one of my TAs), a beloved UChicago tradition where the 2nd year math grad students put on an elaborate skit parodying all the faculty members (whilst said faculty members are in the audience!). It was ridiculous, and wonderful, and I remember thinking to myself with absolute sincerity: ‘These people are really fucking cool – I wanna be around them.’

And of course, I grew to love Maths as well. But that goes without saying.

I’ve typically had a very friendly and chatty relationship with my TAs – though without actually becoming close friends with them. This meant that even after I graduated from college, I still thought about them on occassion. I often let myself wonder about what became of them. The first and obvious question: did they finish their PhDs, and what did they do their theses on? I (being nosey) went onto the ProQuest database and looked up their names. Sometimes I found nothing. But on the occasions when I found their PhD theses in the database, I felt a pinch of excitement and could not resist having a quick peek at what they did. What did all these stress-filled and intense years of grad school cumulate into? What did my mathematical seniors, who seemed so much smarter than I was, accomplish? Some dissertations seemed pretty decent, others seemed … not so good. I found one that was just about 30 pages long: half of it was fairly basic exposition, and the rest was dedicated to proving what appeared to be a fairly simple theorem. Another thesis I read was less than 15 pages long: again, the first 10 pages were basic exposition, with the final 4 pages containing a hurried patchwork of two propositions (which weren’t even originally due to the author) and the final main theorem.

My heart sank, and ached for these people. Suddenly, they became minute. They were no longer aspiring mathematicians brimming with promise, or students whose cheeky antics at Beer Skits caused us all to roar in laughter — now they were merely footnotes, a wry smile, a memory. After being given time to prove themselves, they’ve emerged as some kind of casualty marked by their limitations and the official stamp of a system that did not need them. I found this painful. I wasn’t thinking of myself or prognosticating my academic fate – I was just genuinely sad for them. I imagined their sense of panicked dread as the deadlines drew steadily closer and it seemed increasingly probable that they wouldn’t have much to show for all their hours of effort. I thought of the overwhelming pressure they must have felt as they tried to keep going, or the simple but absolute pain of not being able to execute what they wanted to do. It was all over – there was nothing to do about it. But still, whilst I wasn’t really thinking of myself, this was my first brush with the more unforgiving side of academia. My sadness carried an implicit recognition: You might really love maths, but that doesn’t mean you’re good enough to stay on.

In the years since, more aspects of this sobering reality have filtered through. Recently I’ve been watching Mura Yakerson’s ongoing YouTube series ‘Math-Life balance’ with great interest, where she conducts informal interviews with established mathematicians (though there are exceptions). Some of the interviews I liked and felt reassured by, others I found alienating and slightly painful to listen to. In any case, I still got a lot of out of it. I want to mention one particular interviewee. Saul Glasman, who worked in homotopy theory before eventually leaving for industry, made a remark about how academia was like a pyramid-scheme in that there’s just too many grad students and not enough faculty positions for everyone: only the small minority will make it to the top. This bleak statement about the scarcity of academic positions was one that I’ve heard before, so I wasn’t caught off-guard by it. What I did find interesting was Glasman’s off-hand remark that: “Everyone has a story that they tell themselves, about how they’ll be the ones who make it.”

This is clearly not just true of aspiring mathematicians in academia, but of anyone trying to will themselves to keep on fighting. Glasman’s remark made me think of how Allison Iraheta (an American Idol contestant) claimed that she would ‘set the world on fire’ with her music. Or how many MMA fighters such as Conor McGregor often speak with delusions of grandeur. Or how Mima Ito (a Japanese table tennis player) repeatedly insisted that she would win the Olympic gold medal in all 3 events she was competing in, and end Chinese domination of the sport. Or how Charlotte Eades, who was diagnosed with terminal brain tumour as a teenager, insisted in her YouTube vlogs that she was going to live till she was 90.

The sobering reality reveals a different story. I don’t know whatever became of Allison Iraheta but suffice to say she hasn’t exactly become a household name in music. McGregor suffered devastating losses in 3 of his 4 recent fights, and has scrambled to find reasons to burnish his image as an invincible fighter. Ito did beat China once in the mixed-doubles event, but lost to China in the Women’s singles and Women’s Teams – one post-match interview featured her in absolute tears, trying to compose herself after having lost in 4 straight games to Sun Yingsha. And Charlotte Eades did not live till she was 90 - after 2.5 years of battling cancer, she died at 19, unable to speak or function properly in her final months because of how the brain tumour had spread.

The uninvested bystander is wise to the gap between hope and reality. But the question remains: why do we even tell ourselves these stories in the first place? Why do we tell ourselves things that some small part of us knows sounds delusional?

One answer: people who do this are being naive and foolish, and have decided to ignore reality because it’s too unpleasant to bear. There is certainly truth to this, but it is also glib and misleading. Cynicism in and of itself is not wisdom. Hedging your bets is only risk aversion – it is a reaction to the unknown as opposed to the logical consequence of having correctly apprehended the relevant details of ‘objective reality’. And whilst it is true that many cling to delusions because they find the stark truth too difficult to bear, it is equally true that it takes very little to live a life of passive mediocrity, and that those who are keen to bring others down to their level often do so because they want to avoid the uncomfortable fact they might have settled for second-best. This is why the peanut-crunching crowd does what it does. Just ask David Goggins.

Tuning out the noise of all these defensive reactions reveals the more fundamental reason for such personal narratives: it’s a way to negotiate our relationship with the unknown. The unknown, by its lack of dimensions, appears infinite and untransversable, and by its blackness, portentous with hidden dangers. In the case of navigating academia, there is an unspoken sense that there are accidents just waiting to happen: it feels that so many things have to go right for us to make it, which only creates more opportunities for things to go wrong. Am I going to be able to get the next Post-Doc position? How will COVID-19 affect the academic job market? Who is going to be receptive to my ideas and my research? Everything feels chance-y and unstable. And there’s this nagging thought at the back of your head: is this where my luck finally runs out?

These stories we tell ourselves give us a reason to keep going. Now I would emphatically deny that finding reasons to give up is the same as having understood reality for what it truly is. It takes fairly little talent to throw in the towel — one can always easily find reasons to give up. And yet there may actually come a point where you will have to give up a long-held dream. And there’s an important distinction to appreciate here. It’s one thing to have realised that you’ve given up a dream without meaning to — e.g. perhaps you’ve always dreamt of being a singer-songwriter, or an Olympic athlete, or work for an NGO, but you’ve put these dreams on the backburner so you could focus on other things before suddenly realising one day that these dreams have reached their expiration date without your noticing. But it’s quite another thing to give up a dream that you’ve been fighting to make happen. Both can be deep losses and should be mourned – but there’s a difference between losing something because you didn’t properly try vs. losing something even when you did. The former typically carries a tone of inevitability (even if tinged with regret) because some part of us recognises the finiteness of our time and abilities, the latter feels more damning because we lost even when our eyes were supposed to be on the ball.

In his interview with Mura, Glasman says that we shouldn’t view ourselves as a failure if we end up leaving academia. I absolutely agree. If nothing else, I certainly gained a great deal from having struggled honest struggles when trying to come to grips with new maths, and trying to push my abilities to its limits. I don’t think I’ve wasted my time trying to be a mathematician. But continuing with this thought, it’s also worth me having a proper think about the prospect of leaving academia, no matter how deeply I love maths, because it raises valid and urgent questions about what my priorities are. All this careful balancing requires brutal honesty and consistent courage. I want to build special relationships in my life of all kinds. I don’t want to look back embittered about how I gave up so much of my personal happiness in exchange for an academic career. It’s important for me to live an examined life, but it’s also important for me to live a full and happy life as well. Equally, however, I don’t want to simply throw my hands up and leave the moment things get tough — I don’t want to have to regrets about giving up too soon either.

I want to stay. I am willing to fight to stay. But I also think, it’s important to try and let go of things you cannot control (because that’s a waste of energy and emotions), and focus on the things that you can control. And it’s important not to lose your soul when you try to play the game just to stay in the running.

We all have different stories that we tell ourselves. This isn’t just about that flickering flare of unreasonable hope that keeps us going in the midst of intense difficulty, but also encompasses other aspects of our self-image — the personal, the moral, the political, the romantic, the sexual. I don’t feel comfortable making dogmatic assertions about this right now, but provisionally: whatever the relationships are between these aspects of ourselves, it seems important to not let one aspect dominate or warp the others. It also seems to me that some stories are better than others. Right now, for me, the more useful stories are the ones that call our attention to things we can control and actually do, to hidden aspects of ourselves that may have been quietly developing and gaining strength, to growing wisdom gained from experience. Stories that emphasise agency and maintain a clear-eyed perspective on what to do next as opposed to stories on why we’ll be the ones to make it – these are the stories I find helpful and empowering.

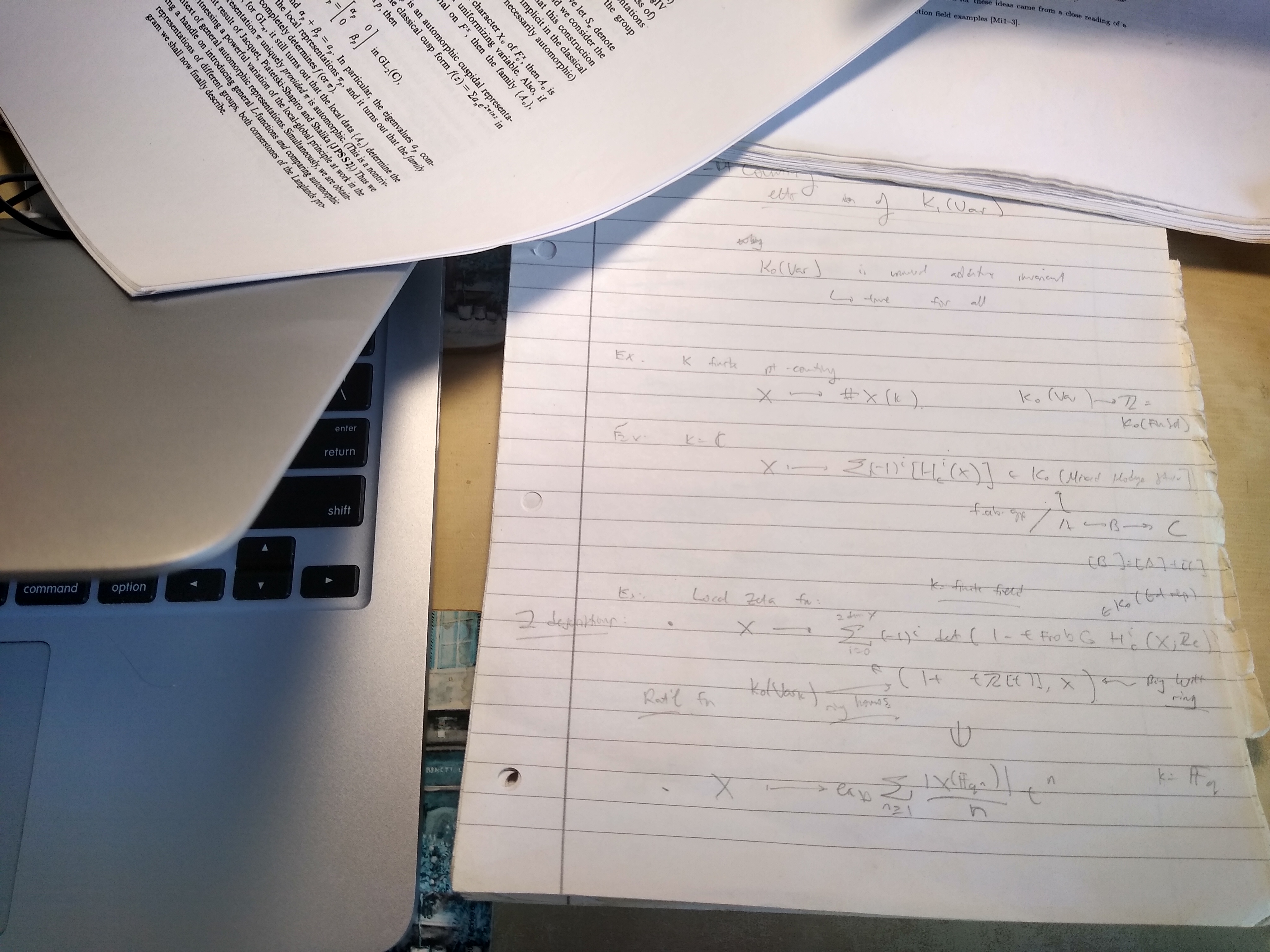

So a thought experiment: suppose I must leave academia at some point, what would I like to accomplish before I leave? Right now, I would like to actually enjoy and cherish the rest of my PhD days esp. since I’ve been given the opportunity to research a topic that I chose myself. I’ve been given considerable freedom to think for myself. I don’t ever want to forget this or take this for granted — even in the midst of the looming stress about the uncertain future, there is still plenty to be grateful for. And if I must leave, I would like to finish writing some papers I’ve always meant to write, because I think these ideas will be helpful in moving the conversation forward in interesting ways. And personally, I would like to grow as much as I can during this time, because this is the one time where the cultivation of one’s mind and abilities is an end of itself as opposed to a means – another privilege.

This is the story I’m telling myself right now. I don’t want to leave. But if I do, then I’m going to do so without regrets or feeling like I’ve left certain things unfinished. I will have done absolutely everything that I could reasonably expect myself to do, and then some. And I don’t want to have wasted time over pointless emotional handwringing, because there’s enough of that. Ultimately, no matter what happens, I want to live a full life with no regrets, and I want to know how to make the next step forward. And this story gives me a clearer sense of how to do just that. Now it’s time to set out a routine in which I can truly do work at my own pace as opposed to just playing catch-up with the world, and where I can allow myself to be guided by the maths as opposed to my fears. I want to cultivate and protect my independence, I want to focus on what matters, and efficiently excise the stuff that doesn’t. Indeed, as I’m sure is clear to the reader, these basic principles don’t just relate to doing maths, but also more generally to how I structure my life. We shall see how this goes. To be continued.

Leave a Comment